Sports. Theatre. Concerts. They all seem to do dynamic pricing these days. If it’s a losing team, slow night, or not yet sold out, venues sometimes drop ticket prices. On the flip side, if it’s in demand, official ticket prices go way up. Whether it’s an Oscar winner or a popcorn blockbuster, as Wired Magazine’s Rafi Mohammed recently speculates, what if movie theaters did the same?

Take a look at the theatre business. Pros for dynamic pricing in the theatre, from what I can tell, mostly benefit the presenting organization (but it doesn’t always have to). Dynamic pricing allows you to sell shows and set prices based on demand. I think of it as a more engaging way to look at the inventory on hand. You constantly have to be evaluating what the market wants. If demand is high for a show, you can raise the prices; while lower-income people won’t necessarily make it to your show, those with higher incomes (who were going to come buy the $80 ticket) will probably buy the $95 ticket. And those minor increases to your bottom line can make huge impacts. Think about it: you’ve already created a budget based on what you expect to sell. If you all of the sudden start making $15 more a ticket in a 2,000 seat house, in one night you’ve made an additional $30,000… which is enough to make up for a low-selling night you had two weeks prior.

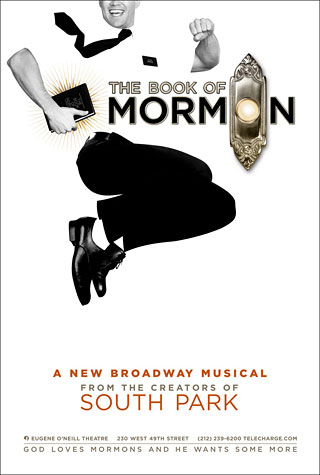

In a weird way, you also create buzz around the show, and your organization. Broadway has done this for years. It’s the reason why “Book of Mormon,” which is from the creators of “South Park,” is selling its premium seats currently for close to $400. All it takes is reading even one random article about the show to know it’s become what everyone wants to see in New York. If people are paying $400, it must be good, right? And if a theatre is constantly producing work whose ticket prices rise, then they must have good taste, right?

It’s also especially good if you think about it the other way. Dynamic pricing allows you to drop the price if you have a show that isn’t selling. If you can’t sell a ticket for $20, by dropping the price even $5, you might convince a skeptical audience to spend the money. They might take a chance, assuming that price change allows you to hit the sweet spot. In theory, even if you can only sell 20 more tickets, that’s an additional $300 in the scenario above. And while monetarily there is not as many pros for the organization in the short term there, you’ve gotten 20 more people in your doors, 20 more people talking about your theatre to their friends, and 20 more people who might just turn into patrons.

Finally, dynamic pricing allows you to do what is a theatre marketers greatest challenge (or one of them), and that’s to sell tickets early in a run. Typically, preview periods and the first week after opening are a tough sell. Reviews haven’t come out, people’s friends haven’t seen the show, and how on earth are you going to get people to come see your show if they haven’t heard anything about it? With the price of the average theatre ticket, you aren’t just going to drop that kind of money on a whim. However, if you have single ticket buyers who seem to come back year after year (students, young adults, young parents, and so on who like your work but don’t have the cash to buy a subscription) who now knows if they wait for the review they might have to pay more, they might be more inclined to buy early. To do some research on their own. To take a chance. This gives the organization some much needed cash up front to pay for the next production.

Movie theatres need to be smart about how they implement this model. Just because “Extremley Loud and Incredibly Close” was nominated for an Oscar, it still doesn’t mean I really think it’s worth paying more money for. However, let’s say I hadn’t seen “The Artist.” All I’ve heard is rave reviews and it won a bunch of awards. If demand remains constant or even increases, now maybe you have some proof people actually would spend some money on it.

Overall, this concept isn’t a new one. Organizations providing goods to consumers have employed this model consistently from the beginning of time. There is only so much inventory to sell, so you find the sweet spot, where your demand meets supply and you’ve therefore maximized profits.

Commentary

Got something to add?